The stakes are Germany’s future, its survival, the protection of its sovereignty, and making Europe competitive and capable of negotiating with Russia, China, and now even the USA. Achieving this will require a ruthless reduction in the standard of living and quality of life of German citizens, and the winning parties will have to forget most of their campaign promises.

The German election is not about whether the AfD will come to power because the traditional political parties—the CDU/CSU on the right and the SPD, the Greens, and the Left Party on the left—can still form a two- or even three-party coalition and continue to keep the far-right, but in reality neo-Nazi, AfD in opposition. Germany’s liberal democracy will get another four years.

The big question is how successfully the governing parties will be able to explain to the German people, once the election is over and political reality sets in, that the promises they made during the campaign—that everything would remain the same or even get better—were not true at all. That the good old days are over, that belts need to be tightened because demand for German goods has declined, Germany is no longer competitive enough, there is a war in Europe, and vast sums must be spent on national defense since the USA is no longer willing to guarantee Europe’s security with American money.

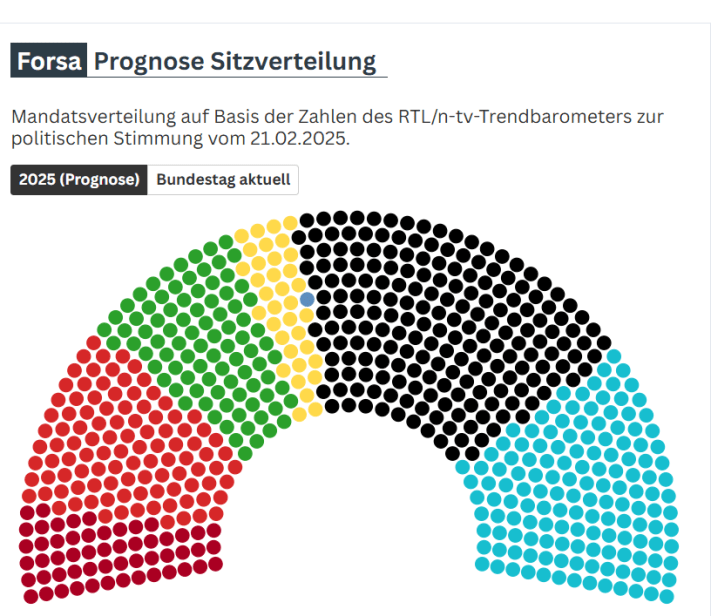

The new election law has reduced the number of Bundestag representatives from 736 to 630. According to the Forsa Institute, the distribution of seats is expected to be as follows: CDU/CSU 200, AfD 145, SPD 104, Greens 90, Left Party 55, FDP 35. The most likely coalition is CDU/CSU-SPD-Greens. Mathematically, a CDU/CSU-SPD-Left Party-FDP coalition is also possible but unlikely. No party is willing to enter into a coalition with the AfD.

All previous right-wing and left-wing miracle solutions can be forgotten—whether it be cutting the social safety net or taxing the rich—because neither can provide a solution in today’s global capitalist system. Borders can be closed, migration slowed, and citizens’ freedoms and social protections restricted for noble or purely selfish reasons. However, stopping the free migration of capital, which respects no national borders, is impossible. If money wants to leave Germany, it will. Or if it stays, and even that won’t immediately be beneficial, it may shift its support to extreme parties like the AfD if its interests are threatened.

A small consolation, but actually a darker omen for the future, is that Germany—the world’s third-largest economy—is in a far better position than France, Italy, Spain, or even the UK, which took a bold leap into the unknown with Brexit. These countries face even greater economic troubles and debt crises. Germany, for a long time, managed to rely on state funds accumulated during years when it did not need to borrow for its operations because tax revenues exceeded government expenditures.

One of the first major post-election steps—after some performative debate—will be to lift the constitutional restriction on increasing national debt. This will be necessary even if Germany, which is not impossible, can return to a path of economic growth and significantly improve its competitiveness through structural reform. The most likely scenario at present is that Germany will resort to unprecedented military expansion—partly due to the Russian threat and the poor handling of the Ukraine crisis by the U.S., and partly by following the traditional formula of shifting economic reliance from the automotive industry to the defense sector.

Whatever happens, it is clear that the standard of living and quality of life for Germans will decline, and the state will have to scale back its social spending. This will not be easy to enforce even within the governing coalition—let alone with the German public, which still refuses to accept that its economic output has been devalued and that, for reasons beyond its control, not only the excesses but even the very foundations of the welfare state must be cut back.

The incoming government faces an almost insurmountable accumulation of problems decades in the making. Adding to this is the economic and social emergency in nearly every European country. Although migration is not the root cause, it is one of the most visible factors through which society perceives the contradiction between economic performance and state benefits. The rising far-right will ensure that this remains a central issue.

In addition, the European Union itself is facing serious challenges, including the rise of nationalist “our country first” policies and growing resistance to the crucial need for a unified European response. Overcoming this will depend on French-German leadership—if it can be overcome at all. Perhaps the post-election German government will inject new energy into this effort, given that the outgoing government failed on this front as well.

Looking at Germany alone, the international climate and recent global events only further complicate the situation. Germany and Europe must find their place alongside and against the USA, Russia, and China. This requires better economic performance, stronger military forces, and a common European economic, foreign, and defense policy. Additionally, the EU must restructure internal capital flows to revive the European economy. And—given the strength of labor unions in countries like France and Germany—it must also ensure social stability.

The Stakes of Sunday’s Elections in Germany

The stakes are Germany’s future, its survival, the protection of its sovereignty, and making Europe competitive and capable of negotiating with Russia, China, and now even the USA. Achieving this will require a ruthless reduction in the standard of living and quality of life of German citizens, and the winning parties will have to forget most of their campaign promises.

The German election is not about whether the AfD will come to power because the traditional political parties—the CDU/CSU on the right and the SPD, the Greens, and the Left Party on the left—can still form a two- or even three-party coalition and continue to keep the far-right, but in reality neo-Nazi, AfD in opposition. Germany’s liberal democracy will get another four years.

The big question is how successfully the governing parties will be able to explain to the German people, once the election is over and political reality sets in, that the promises they made during the campaign—that everything would remain the same or even get better—were not true at all. That the good old days are over, that belts need to be tightened because demand for German goods has declined, Germany is no longer competitive enough, there is a war in Europe, and vast sums must be spent on national defense since the USA is no longer willing to guarantee Europe’s security with American money.

The new election law has reduced the number of Bundestag representatives from 736 to 630. According to the Forsa Institute, the distribution of seats is expected to be as follows: CDU/CSU 200, AfD 145, SPD 104, Greens 90, Left Party 55, FDP 35. The most likely coalition is CDU/CSU-SPD-Greens. Mathematically, a CDU/CSU-SPD-Left Party-FDP coalition is also possible but unlikely. No party is willing to enter into a coalition with the AfD.

All previous right-wing and left-wing miracle solutions can be forgotten—whether it be cutting the social safety net or taxing the rich—because neither can provide a solution in today’s global capitalist system. Borders can be closed, migration slowed, and citizens’ freedoms and social protections restricted for noble or purely selfish reasons. However, stopping the free migration of capital, which respects no national borders, is impossible. If money wants to leave Germany, it will. Or if it stays, and even that won’t immediately be beneficial, it may shift its support to extreme parties like the AfD if its interests are threatened.

A small consolation, but actually a darker omen for the future, is that Germany—the world’s third-largest economy—is in a far better position than France, Italy, Spain, or even the UK, which took a bold leap into the unknown with Brexit. These countries face even greater economic troubles and debt crises. Germany, for a long time, managed to rely on state funds accumulated during years when it did not need to borrow for its operations because tax revenues exceeded government expenditures.

One of the first major post-election steps—after some performative debate—will be to lift the constitutional restriction on increasing national debt. This will be necessary even if Germany, which is not impossible, can return to a path of economic growth and significantly improve its competitiveness through structural reform. The most likely scenario at present is that Germany will resort to unprecedented military expansion—partly due to the Russian threat and the poor handling of the Ukraine crisis by the U.S., and partly by following the traditional formula of shifting economic reliance from the automotive industry to the defense sector.

Whatever happens, it is clear that the standard of living and quality of life for Germans will decline, and the state will have to scale back its social spending. This will not be easy to enforce even within the governing coalition—let alone with the German public, which still refuses to accept that its economic output has been devalued and that, for reasons beyond its control, not only the excesses but even the very foundations of the welfare state must be cut back.

The incoming government faces an almost insurmountable accumulation of problems decades in the making. Adding to this is the economic and social emergency in nearly every European country. Although migration is not the root cause, it is one of the most visible factors through which society perceives the contradiction between economic performance and state benefits. The rising far-right will ensure that this remains a central issue.

In addition, the European Union itself is facing serious challenges, including the rise of nationalist “our country first” policies and growing resistance to the crucial need for a unified European response. Overcoming this will depend on French-German leadership—if it can be overcome at all. Perhaps the post-election German government will inject new energy into this effort, given that the outgoing government failed on this front as well.

Looking at Germany alone, the international climate and recent global events only further complicate the situation. Germany and Europe must find their place alongside and against the USA, Russia, and China. This requires better economic performance, stronger military forces, and a common European economic, foreign, and defense policy. Additionally, the EU must restructure internal capital flows to revive the European economy. And—given the strength of labor unions in countries like France and Germany—it must also ensure social stability.

Hungary: A Spectator to the Crisis

In light of all this, Hungary can be said to be unaffected by these issues because, de facto, it is no longer part of the Western world. Although it remains economically dependent on Europe, its government resents this and prefers to seek future economic ties with China while politically aligning itself with Russia and the USA. The Orbán government has positioned itself against the entire EU, withdrawn from NATO’s Ukraine-supporting efforts, and is openly hostile toward Ukraine.

It is fair to say that while Hungary remains a de jure member of the EU and NATO, it is no longer aligned with them and is instead acting against them. Hungary is politically adrift, desperately seeking allies worldwide. So far, it has only managed to embed itself in Europe’s far-right camp, with its ruling party, Fidesz, becoming a leading voice in attacking the West and its democratic institutions.

No revolutionary change is expected before 2026, and even then, it is uncertain whether an election defeat—if elections are even held—would lead to Orbán losing power. Hungary has become so undemocratic, and its institutions have been so thoroughly dismantled, that a mere opposition victory would not be enough. Without dismantling the regime’s structures—an act that cannot be done legally—any temporary setback for Orbán would likely be followed by an even harsher comeback.

Ironically, due to Orbán’s reckless foreign policy, Hungary is now in the “best” position in Europe—because, no matter what happens, it will lose. If Europe fails against the USA, Russia, and China, it will be a disaster for Hungary’s economy, which is entirely dependent on Europe. If Europe emerges from this crisis successfully, Hungary will pay a heavy price for its anti-European stance and its alliances with Europe’s adversaries.

In short, Orbán’s balancing act—trying to be both inside and outside Europe—will end in a knockout. Hungary will fall flat between two chairs: one it kicked out from under itself, and the other it never had a chance to sit on in the first place.

— Zsolt Zsebesi